BIRKA WALLET

Or coin purse.

When found, the original wallet was crumpled up and confusing, so it involved interpretation from the beginning. It is filled with interpretation and extrapolation; if you want to change any of the details, feel free.

The wallet dates from between the ninth and the eleventh centuries, and the wallet was discovered in 1879 in grave bj750 from Birka. “This type of bag is a folded wallet of goat leather with multiple compartments on the inside. They were decorated with strips of gold plated leather, which was woven through the leather to form a checker board pattern. Along the edges were gold plated loops, 0.7cm long and 0.5cm wide.” // // I did not even attempt to duplicate any of these ornamentations, but that was merely my choice.

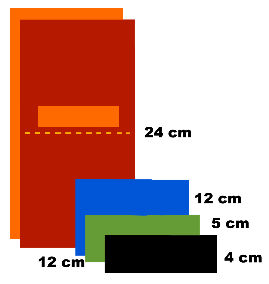

A Birka wallet consists of five pieces of leather, cut into rectangles of various sizes. They should be aligned at the bottom and then stitched together so that the bottom is five layers deep, while the top is only two. In the second layer, the leather is cut so that there is a rectangular slit, and the leather itself forms a pocket. Sone people duplicate it with interior stitching and the leather turned inside out when sewn, but I sewed the layers with a locking stitch. Some prefer to use two needles at the same time, though I find sewing each side in succession. I punch holes for the sewing using an awl.

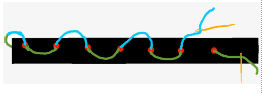

Cut the thread into a length that is twice as long as you need. Loop it at the end, and then bring the needles into the holes pierced, first on one side and then at the other, and knot it at the other end (in the diagram, the same strand has two colors merely to distinguish the difference).

The first time I tried to make a wallet, I used slightly thicker leather. The end result was more or less unuseable. I tried to use lighter leather the next couple years and was finally satisfied with leather about 2–3 ounces thick.

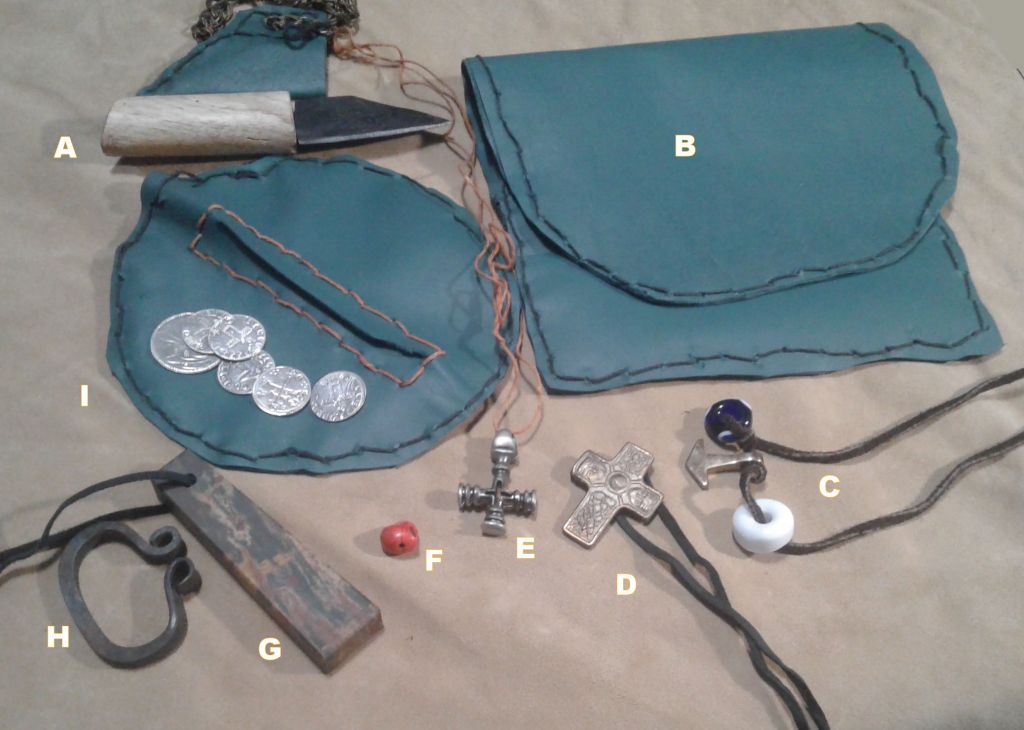

The wallets seem to have been concealed under robes or tunics. They were neither worn nor displayed on the outside. After acknowledging this, it occurred to me that I needed to stuff the wallet with what was commonly found in them. So…

Clockwise from top left: A) Small utility seax; B) the Birka wallet; C) A couple beads and a Mjollnir from Repton; D) a Cross; E) a Fenris cross/Mjollnir (what I call the Hedge Your Bets Cross); F) a souvenir stone; G) a strike-a-light; H) a whetstone (jasper); and I) a coin purse with a few coins. Everything a Viking needed when he was on a raid!

LOOK UP IN THE AIR

Mankind has been fascinated by the flight of birds for Millennia. The possibility and attraction of human flight dates from at least the legend of Icarus in 60 bce. However, it was seen only as a legend, perhaps myth, until the tenth or eleventh century.

Eilmer of Malmesbury (who was also known as Elmer, Æthelmær and, because of a scribal error, Oliver) was a Benedictine monk from England. It has been suggested that he was born about 980 ce and that his attempt at flight took place sometime between 995 and 1010 ce. In his youth, he had read and believed the Greek myth of Dædalus, and he attempted to make and wear his own glider wings.

William of Malmesbury in the Gesta Regnum Anglorum of the early twelfth century noted that “He was a man learned for those times, of ripe old age, and in his early youth had hazarded a deed of remarkable boldness. He had by some means, I scarcely know what, fastened wings to his hands and feet so that, mistaking fable for truth, he might fly like Dædalus, and, collecting the breeze upon the summit of a tower [of Malmesbury Abbey], flew for more than a furlong. But agitated by the violence of the wind and the swirling of air, as well as by the awareness of his rash attempt, he fell, broke both his legs and was lame ever after. He used to relate as the cause of his failure, his forgetting to provide himself a tail.” It has been conjectured that his flight that the flight was only about 15 seconds. (In 1903, the Wright’s first non-glider flight was about 59 seconds.)

Modern calculations by Paul Chapman confirm the feasibility of the flight. “Launching into the southwest wind his initial descent would enable him to gain sufficient speed so that he could ride the air currents off the hillside. Lack of a tail would make continuing to head into the wind difficult and he would have been blown sideways to land where legend suggests—Oliver’s Lane.” Despite his injuries, “Eilmer set about rectifying this shortcoming, and was making plans for a second flight when his abbot placed an embargo on any further attempts, and that was that. For more than half a century after these events, the limping Eilmer was a familiar sight around the community of Malmesbury, where he became a distinguished scholar.”

Were there other and later (or even earlier) attempts at human flight before Leonard da Vinci’s drawing of a glider in the fifteenth century, though his physical attempts, if any, are unknown.

The unsuccessful attempt by Eilmer is fascinating but little known, and one can relate the story to MoPs at an event, accentuating the mechanics of the attempt, the attempt itself or how a near-sighted abbot’s attempts to keep his flock safe retarded the discover of aeronautics for a few hundred years. I would love to see the reconstruction of the wings at an event, although at the risk of sounding like that abbot, I might not want to see a physical attempt at the event!

BASKETRY OF THE VIKING AGE

A recent thread on a Regia newsgroup concerned questions about baskets—specifically types—of the Viking age. In it, there were plenty of extrapolations, suggestions and suppositions. Almost no hard evidence, that is, extant baskets of the time.

On one hand, we know they had baskets. There are fragments of basketry, and “The history of weaving containers with plant fibers likely goes back to the start of mankind. Unfortunately, plant fibers often have a hard time surviving in the soil that long or even as far back to the late 8th Century at the start of the Viking Age.” A ten-thousand year old basket miraculously survived—and it is not significantly different from those of later ages—was found is Israel, and we are told ““Organic materials usually do not have the ability to survive for such long periods,” Dr. Naama Sukenik from the IAA’s Organic Material Department told The Jerusalem Post. “However, the special climatic condition of the Judean Desert, its dry weather, have allowed for dozens of artifacts to last for centuries and millennia.”

There are a few extant samples of baskets from our periods, We know from extant baskets thAt they were both round and square, sometimes with solid bases and tops, made out of willow and other natural substances. We are not certain if they were painted, and we can only make conjectures about whaT they contained, since none have been found with a a content. A few logical extrapolations can be made by examining later baskets and noting that they did not significantly change, but that is closer to experimental archaeology than to anything else. Ironically, the basket weaving techniques founds in extant ancient Roman basketry, in later basketry and even in North American basketry—such as the several basket fragments ound in Binderbost in Washington State do not differ thAt much despite the time and geographic differences.

Here are a few of the baskets that we know existed.

Fragments are known to exist from Oseberg, though there is a tendency to mistake these are being from Gokstad, and these fragments are even often included with pieces of the Gokstad back pack..

The so-called Gokstad back-pack is generally acknowledges to be a basket, though no samples of the basket weaving is available. We are left with the solid wooden top and bottom, and holes for the strakes to be inserted. Weaving a basket around these strakes is logical and easily done, but there are no existing, real samples. In fact, some writers insist that no basket weaving was used at all, and the pack was enclosed by leather. In fact, plenty has been extrapolated, but very little has been proven.

A rectangular wicker basket top has been found in Coppergate. It has been suggested that it ws a pigeon coop basket.

Many of the woven baskets we have come from fishing baskets. They were submerged in mud that helped to present them!

Finding extant samples are difficult, even though many authors love to lecture us that they have been found, though without any documentation or provenance. It is like the subject of tattoos in ma ways; though statements and claims are frequent, solid evidence is sadly lacking. If you have any other sources of photos or descriptions other than those listed here, please let me know.

A GLOSSY ARTICLE

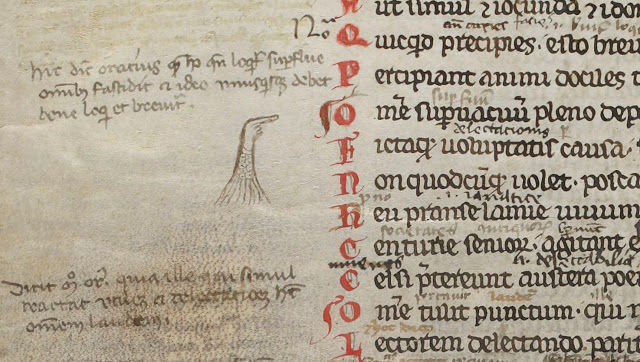

Today, we are warned not to mark in our books (there are, of course, many who will do it anyway). However, in the middle ages, owners of books were encouraged to mark in their books. This was called a gloss or glossa and is specifically an annotation written on margins or within the text of manuscripts specifically of the Bible. Jerome (though he was probably not the translator) used glosses in the process of his translation of the Latin Vulgate Bible.

The subjects of explanatory glosses may be reduced to the following glosses.

• Foreign words

• Dialectical terms

• Obsolete words

• Technical terms

• Words employed in an unusual sense

• Words employed in some peculiar grammatical form

These glosses were written between the lines of the text or in the margin of manuscripts. The glosses originally consisted of only a few words, but they grew in length as authors enlarged them with their own comments. Eventually, manuscripts had so many glosses that there were no longer room to write them in the book. These glosses were compiled in separate books, known as lexicons. But this was not common in England until the fifteen century. “So great was the influence of the Glossa ordinaria on biblical and philosophical studies in the Middle Ages that it was called ‘the tongue of Scripture’ and ‘the bible of scholasticism’.”

A splendid book on glosses has been recently published, though it deals only with the glosses of the Lindisfarne Gospels. Eleanor Jackson’s The Lindisfarne Gospels: Art, History and Inspiration is published by British Library. The Lindisfarne, and other earlier copies of the Bible, were written in the Latin that was known as the Vulgate. However, Jackson notes that “In the tenth century an Old English translation was added between the lines, which I the earliest surviving translation of the Gospels into the [Old] English language.”

Secular interlinear glosses developed from the Biblical glosses but dealt with secular writings. While translations date back to ancient times, glosses do not appear to have been used. The translations were separate sections—for example the Rosetta Stone—and as noted above were later separate books. Secular glosses seem to date only from the eleventh century.