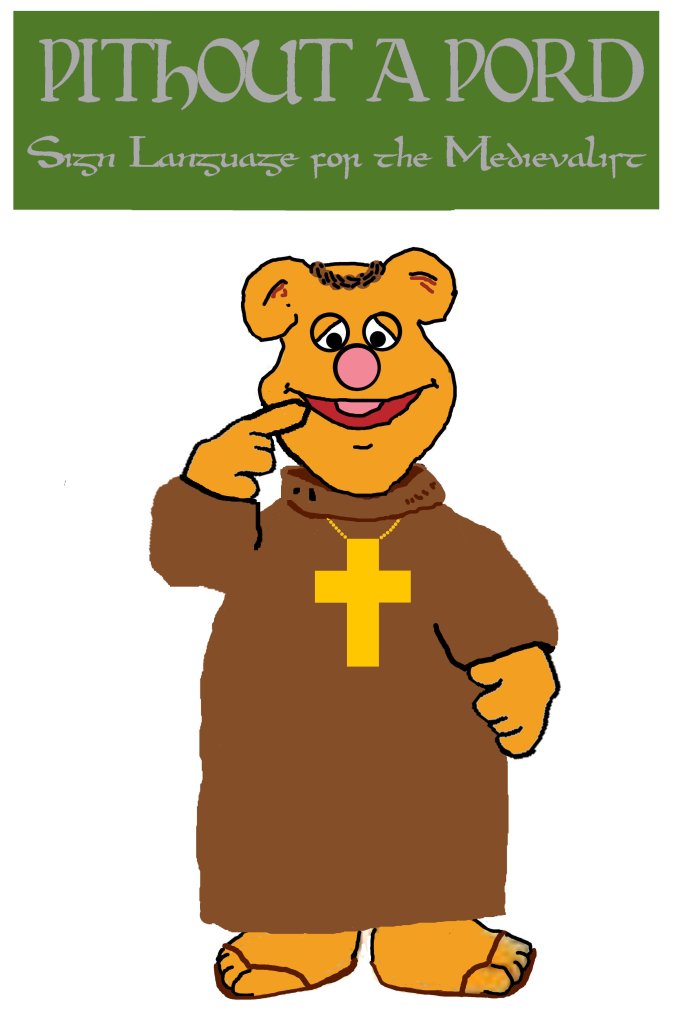

WITHOUT A WORD II: DRINK

Monastic sign language has been used in Europe from at least the tenth century by monks of the Benedictine Order because “silence is a virtue.” It was a method using a hand lexicon to name certain commonplace things without speaking aloud. It is not a language, per sé, like ASL, though very useful. This article was inspired by Debby Banham’s The Anglo-Saxon Monastic Sign Language.

When you wish to drink, lay your forefinger along your mouth.

PROJECTS FOR THE PANDEMIC III: IRONING TIME

There is still controversial whether the whalebone plaques that have been found are designed for ironing clothes or for other reasons. I am fairly certain they are designed for ironing. Then, I randomly found some Viking Era glass irons/linen smoothers, and that made me determined to make an ironing board! Historical Glassworks had two types of period irons. Only one style seems to be in stock right now, but the other was a tear-shape iron that is cute as dickens, so I’m glad I got both! 🙂

That meant that I needed a plaque. Making it of whalebone was out of the question. Legal–ie, vintage–whalebone (or ivory) was too expensive even if you cannot find a suitable selection. I went to my favored supplier of faux ivory, Masecraft Supply and ordered a sheet that was 8x10x½ (inches; 20.3×25.4×1.3 centimeters). The sheet was very satisfactory, so now I had to decide on a suitable rendition.

Most of the plaques I have seen were dragon heads, such as that found in the Scar boat burial in the Orkneys. However, I doubted my personal ability to do the shaping, and besides, I was afraid the dragon heads might snap off while being transported from site to site. I ended up designing the plaque like that kept at the University of Cambridge. The result was simple but functional and could no doubt be handled roughly with no fears. However, the color was still a bright, glistening white. I wanted to dull it a bit but feared overdoing it. I at last decided to dunk it overnight in a tea dye bath.

I had never dyed faux ivory, so I was not certain of the reaction it would have. The dulling was subtle but pleasing, and it got rid of the glistening shininess that I disliked.

DUPLICATES, REPLICAS, VAGUE COPIES & WHO CARES—LET’S HAVE FUN!

At its core, living history is a serious recreation of an earlier culture. It is not fantasy LAMP, though many such societies brag about how they are true living and those societies who have written authenticity (I prefer the term “accuracy”) rules are just anal and judgmental. Interpretation of what is “thenty” varies; that is why there are so many similar but different societies, many across varying eras (I call them “Fellow Travelers”). But any living-history society that can legitimately style itself by that name has three things in common:

1 Everything is has “on the line” has a historical inspiration, either an actual artefact from the time or a literary description. Most societies demand two or three instances, which is why most Norse societies are not over run by people with bronze Buddha!

- Reenacting equipment are made from historically accurate materials, so that—in the case of the early Middle ages—members are not using cotton, polyester or plywood.

- They do not mix different eras or too many uncommon items unless they use items recycled from an earlier era or an expensive, uncommon item is unique and not universally seen if a low status impression is being depicted.

Beyond these matters lies the exceptions of them, and they differ widely. Whether the reenactors have first- or third- (or even second-) person impressions, or even if they talk modern English (or the language of the main surrounding culture) are entirely dependent mainly on the society. But some of the elements mentioned below make it completely not living history, though others have a grey area. . Some are fairly standard and wide spread, such as blank ammunition, rebated combat blades and no lead drinking vessels. We will deal with the extent of these exceptions below. But first, let’s look at the five common levels of accuracy…

Museum-Quality Duplicates

Every object used or displayed is an exact duplicate of an historical object down to how it was made. It is a duplicate that could be found in a museum, and anything that does not differ in any extent—great or not, materiasl, design, tools—that were not used on the original. To a good extent, this is experimental archaeology.

What You See Is What is Accurate

The visible parts of every object used or displayed is an exact duplicate of an historical object, but unseen, interior seams are not necessarily by hand, non-period details—such as grommets—might be hidden and non-period tools are used.

Objects are Inspired by Artefacts

While an object is inspired by an existing artefact, the replica may be made of a different material (but nothing that was unavailable) and different sizes but still has the general shapes and adds no features no features that were unavailable such as rope handles and plastic hinges. The use of things that cannot be provenanced such as leather hinges.

The extent of these modifications are determined by the society’s Authenticity Officer (AO), and any modification cannot be unilateral and must be approved by the AO. In some cases, something that was permitted is now forbidden and must be replaced or just eliminated by a certain time.

Many societies have degrees of innovation, where a practical change is made that is related to an example but possible…but have the AO approval before making or displaying it!

Items Are Medieval-esque

Items are vaguely based on what is true, but it is more important to look neat and cool and almost as if you stepped out of a Mel Gibson film. At this point, it is usually bit uncertain whether it is living history or not.

If They’da Haddit. They’da Usedit if it was Cool

The “reenactor” eschews all research and does what he wants because fancy-dress cosplay is more important than anything else. This is, of course, definitely not living history.

In Conclusion

None of the above are absolute black and white, and every aspect may be fudged, debated and debated. In addition, you and your society has its own standards. Having farby standards is not bad if you and your members agree to it and unless members of your society object to being surrounded by farb or you brag about how thenty it is. However, each should be in your mind and neither ignored nor even considered.

PROJECTS FOR THE PANDEMIC II: CHESS

While it is generally assumed that chess was not period for the Viking Age, it had actually been introduced into Europe and, in fact, England, by the middle of the eleventh century. We are told by Snorri Sturluson that “As the legend goes, after a celebratory feast at Roskilde, Canute and Ulf [Þorgilsson, a jarl] argued over a game of chess.” Some insist that hnefatafl was meant, but chess had been working up its way from Rome by that time!

The most famous of the Viking Era chess sets—though it dates from the twelfth-century, sometime after an accepted date for the end of the Viking Age—was Lewis chessmen, which were found in 1831. The chessmen display Norse styles and are splendidly charming! I saw them at a special exhibition in the British Museum, and bough I wanted to buy a set, the sets offered were all plastic. Any sets found in the next few years were either inexpensive plastic or much more expensive thenty materials.

This year, I found a set that was made of plaster. Certainly not as accurate as the walrus ivory used in te originals, but still not plastic. I bought them, and I was delighted by them, as was my wife. There was even two extra copies of the Queen—my favorite piece—so I have it on my desk, and my wife had one on hers. I keep the set in a specially designed wooden chest.

After hugging the pieces for a while, I realized that I needed a chessboard. A standard modern chessboard was not adequate, despite how sophisticated it might be. There were no extant chessboards from most of the middle ages, so I had to go by the boards seen in illustrations from the Crusades. I chose one and made a suitable chessboard. The result was pleasing!

The rules for playing medieval chess differ slightly from those for playing modern chess. A good introduction may be found in https://www.academia.edu/11786901/The_Medieval_Game_of_Chess_A_Guide_to_Play?auto=download .

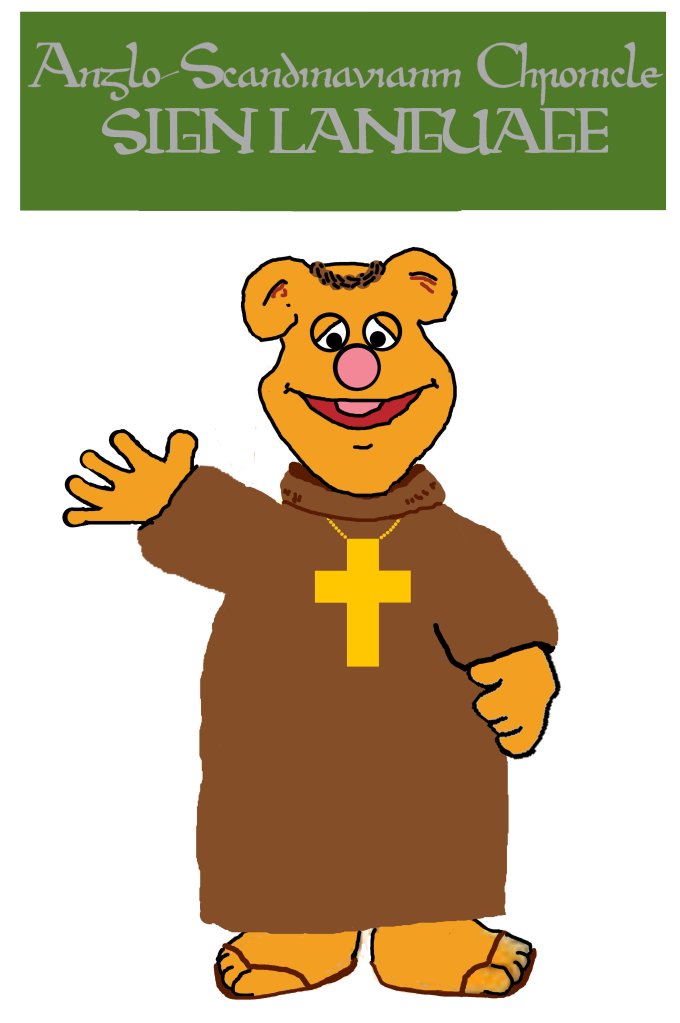

WITHOUT A WORD I: DISH

Monastic sign language has been used in Europe from at least the tenth century by monks of the Benedictine Order because “silence is a virtue.” It was a method using a hand lexicon to name certain commonplace things without speaking aloud. It is not a language, per sé, like ASL, though very useful. This article was inspired by Debby Banham’s The Anglo-Saxon Monastic Sign Language.

If you need a dish, raise up one hand and spread your fingers.